What is Silent Migraine?

Overview

A silent migraine, also known as an acephalgic migraine, is a type of migraine that presents with the typical aura phase of a classic migraine but doesn’t include head pain. Silent migraine is also referred to as aura without headache.13 A silent migraine may also include the prodrome and postdrome symptoms of a common migraine but without the head pain, most commonly associated with a migraine attack. Silent migraine occurs in 5% of the migraine population and the diagnosis is more common in people after the age of 50.1,2

In the video below from the 2019 Migraine World Summit, Nim Lalvani, now Nim Singh, former director of the American Migraine Foundation, further explains silent migraine and why it is often misunderstood.18

In a 2023 interview with neurologist Dr. Nazia Karsan, a postdoctoral clinical fellow of King’s College in London, Lisa Horwitz of the Migraine World Summit illustrates how debilitating migraine symptoms, beyond head pain, can be.11

I find that the accompanying symptoms can be even more disabling than the pain. A person can get used to the pain, but it’s hard when you’re not cognitively at your best, and you still have to work, or parent, or drive a car.

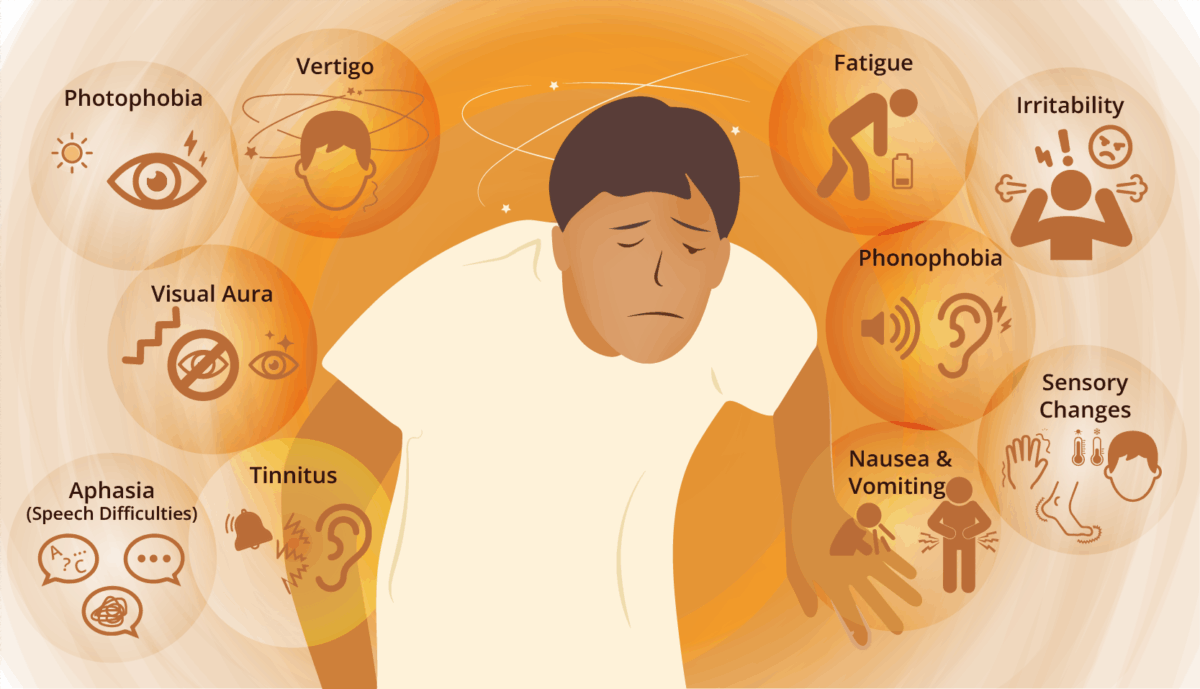

Symptoms of Silent Migraine

A range of disabling symptoms are possible, affecting various senses. Several of the most common symptoms of silent migraine attacks are explained below.8

- Visual disturbances: Also known as scintillating scotoma, includes flashing lights, zigzag patterns, or blind spots.

- Sensory changes: Tingling, numbness, and hot or cold sensations — especially in the face, hands, and feet.

- Speech difficulties: Also known as aphasia, includes trouble finding words or speaking clearly.

- Dizziness, vertigo, or tinnitus: A sensation of spinning, losing balance, or ringing in the ears.

- Nausea and vomiting: Feelings of sickness without any apparent cause.

- Photophobia and phonophobia: Sensitivity to light and sound.

- Irritability: feeling grumpier than usual, easily aggravated.

- Fatigue: experiencing extreme tiredness.

Phases of Silent Migraine

Silent migraine may or may not present with phases.

Like a migraine attack with head pain, a silent migraine may be preceded by symptoms known as the prodrome phase. This phase can start anywhere from a few hours to a few days before a person experiences a silent migraine attack or aura.

1) Migraine Prodrome

The migraine prodrome may express with any or several of the following symptoms, up to 24 hours before an aura:

- Irritability

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Excessive yawning

- Urinating more than usual

- Trouble sleeping

- Food cravings

- Nausea

- Increased sensitivity to light or sound

- Difficulty concentrating, reading, or speaking

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Hyperactivity

2) Migraine Aura

This is the second phase of a migraine for those who experience migraine with aura. Migraine aura can induce various changes throughout the body, including: visual aura (such as flashing lights or zig zags), sensorimotor aura (such as tingling, numbness, or weakness), and dysphasic aura (such as mumbling or slurred speech).

A person diagnosed with vestibular migraine may have aura symptoms of dizziness or vertigo. If they experience these symptoms without the accompanying head pain, it is considered a silent migraine.10 For a person diagnosed with abdominal migraine, a silent migraine may include loss of appetite, nausea, or vomiting, but no head pain.

A person diagnosed with visual aura and silent migraine may see wavy lines, bright lights, flashing dots, or sparkles. These may seem to start in the center of a person’s line of sight and spread to both sides of their field of vision. Silent migraine with visual aura may also include blind spots or scotomas, but with no accompanied head pain.

In an interview with Carl Cincinnato from the 2019 Migraine World Summit, neurologist Dr. Shazia Afridi further describes aura symptoms.

3) Head Pain?

No, a defining characteristic of silent migraine is a lack of the throbbing head pain that is a hallmark of a typical migraine attack.

4) Migraine Postdrome

The last phase of silent migraine is the postdrome phase. Not everyone with silent migraine will experience a postdrome. For those who do, the postdrome phase can include feelings of euphoria for some people. For others, feelings of depression can occur, or symptoms similar to those experienced during a hangover from excess alcohol consumption. A postdrome can last anywhere from a few hours to a few days.

Postdrome symptoms may include:

- Fatigue

- Body aches and sore muscles, such as a stiff neck

- Difficulty concentrating or brain fog

- Nausea

- Light sensitivity

- Sound sensitivity

- Dizziness

- Mood changes, ranging from euphoria (extreme happiness) to depression

Did you know?

Did you know a silent migraine can last anywhere from a few minutes up to several hours?13

Silent Migraine Triggers?

Silent migraine shares many of the same triggers as common or classic migraine, such as:3

- Weather changes and extreme weather conditions including bright sunlight, high humidity, sudden shifts in temperature or barometric pressure, and storms

- Foods and drinks including alcohol, chocolate, and nuts, as well as those foods containing the amino acid tyramine (found in red wine and aged cheese), artificial sweeteners like aspartame, artificial coloring, and additives.

- Environmental factors such as bright or flickering lights, and sudden or loud noises.

- Physiological changes such as hormones during menstruation, pregnancy, or menopause; low blood sugar; and dehydration.

- Sleeping too much or too little.

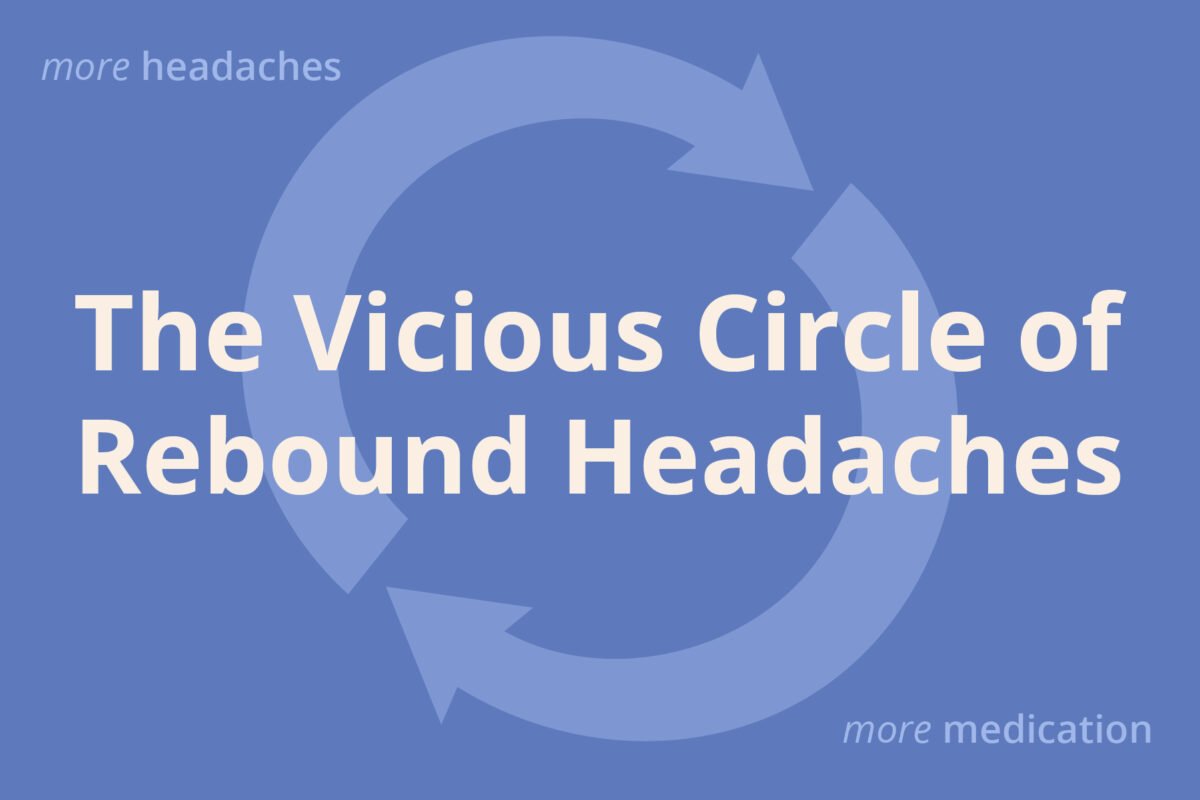

- Medication overuse headache.

- Stress due to sensory and emotional overload, or physical exhaustion.

Headache experts say keeping a daily diary is an important step in diagnosis and in understanding silent migraine triggers. By tracking what a person eats and drinks, changes to their sleep, as well as their hormones, stress levels, and other possible triggers, a diary makes it easier to properly diagnose silent migraine and prevent future migraine attacks. Silent migraine attacks and visual aura are highly correlated, and research is continuing to improve our understanding of this correlation.6

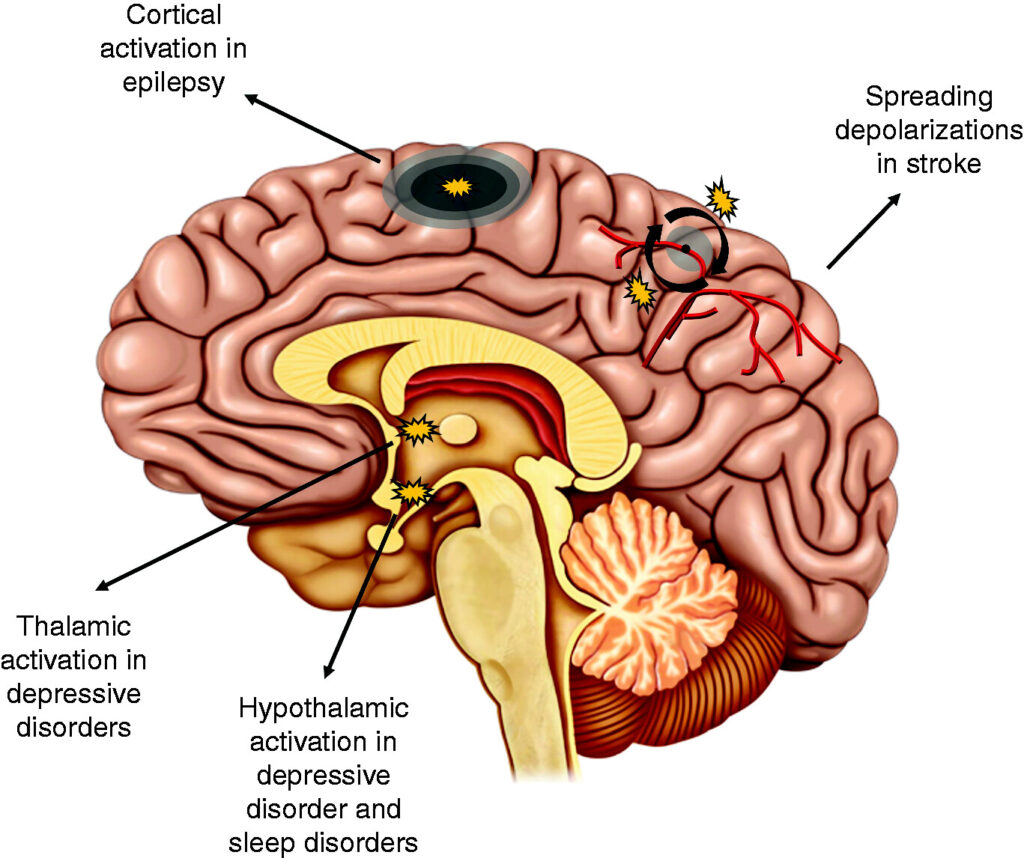

Silent Migraine Causes

Similar to what causes common migraine, migraine aura without headache develops due to a combination of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors, some of which remain unknown. Variations in many genes have been found to be associated with the development of migraine with and without aura, and migraine tends to run in families. Most of the associated genes are active in the vascular smooth muscle in the brain.

Cortical Spreading Depression (CSD) is linked to aura with migraine.1 It is believed that CSD is also a factor in silent migraine. CSD happens when brain cells in the cerebral cortex become hyperactive and then become inactive in a wave that spreads across the cortex. This decrease spreads across the top layer, or cortex, of the brain. It often travels from the visual part of the brain (occipital lobe) to the body sensation part of the brain (parietal lobe) to the hearing part of the brain (temporal lobe) and is linked to blood flow and changes in serotonin levels.3

The cerebral cortex is the outermost layer of the brain’s nerve cell tissue, also referred to as gray matter. Researchers believe genetic mutations may cause CSD that leads to migraine aura. Some of the factors that may contribute to CSD include:

- emotional stress

- hormonal fluctuations

- changes to sleep (including oversleeping or not getting enough sleep)

- weather changes

- exposure to bright lights, loud sounds, or strong odors

- skipping meals

In an interview with the Migraine World Summit, Carl Cinncinato asks neurologist, ophthalmologist, and board-certified headache specialist Dr. Kathleen Digre: “Is it the electricity that’s the change that’s causing the cortical spreading depression or is it a lack of blood flow or something else?”

Dr. Digre says: “What’s interesting is that it is sort of an electrical slowing instead of a seizure. If somebody has a seizure or epilepsy, they have firing of their neurons causing the seizure, but this is something different. Things slow down. There’s this slow wave that goes across the brain, and there are vascular changes that do occur in … There’s some fascinating videos that show this coupling of the slow wave with the vascular changes that are present in the brain, and I think it’s something that’s been demonstrated, for example, in the cortex of other animals.”

Who Gets Silent Migraine?

Silent migraine, or aura without headache, is a subset of migraine. It occurs in 4-5% of patients with migraine regardless of gender. For people who have migraine with aura it may occur at some point in 38% of patients. Typical aura without head pain commonly presents as visual aura. It may also present as a brainstem aura without head pain, presenting as slurred speech, ringing in the ears, impaired hearing, uncoordinated movements, and vertigo. When silent migraine develops later in life, it is classified as late-onset migraine.4

Did you know?

Did you know migraine, including silent migraine, is more common in women? This is believed to be due to female hormones, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause.16

Diagnosing Silent Migraine

Silent migraine can present similar to other conditions because it lacks the head pain that goes along with a classic or common migraine. For example a person with migraine who has been diagnosed with brainstem aura may experience the following symptoms:9

- Dysarthria (slurred speech)

- Vertigo (feeling of movement/spinning of self or environment)

- Tinnitus (ringing in ears)

- Hypacusis (impaired hearing)

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Ataxia (unsteady/uncoordinated movements)

- Decreased level of consciousness

In rare cases, a person’s symptoms may be a sign of a different or more serious medical problem, such as a stroke or bleeding in the brain. In order to rule out other, more serious or life threatening, medical conditions, healthcare providers diagnose silent migraine by doing a physical examination and may perform neurological testing, such as CT or MRI scans.

During the 2023 Migraine World Summit Dr. Karsan shared that the onset of symptoms is often what may provide the biggest clue.11

She says, “I think the onset is very important. So, if it’s like a very sudden one minute I’m fine, the next minute I have a symptom, that’s always of concern. I think the evolution of those symptoms is really important. So, do they just come and then stay fixed, or do they sort of move around and spread?”

She further explains, “Aura is much more likely to have this sort of spreading phenomenon where, for example, tingling can start in one area and then spread up the arm and down the leg, for example, over some minutes. That’s less likely to happen with a stroke than it is with aura. But I would say generally my rule is if you have something that’s new and focal that you’ve not had before, you should seek attention.”

And Dr. Karsan has special advice for older people. “If you have something that you think is aura, but you’ve never had an aura before, and you are over 50, that’s something that should seek attention.”

Comorbidities of Silent Migraine

Several neurological and psychiatric disorders often coincide with silent migraine5. These comorbidities include:

- Depression and anxiety

- Mood disorders

- Epilepsy

- Neuronal hyperexcitability

- Sleep disorders

Treating Silent Migraine

Silent Migraine and Thresholds

Because migraine is considered a threshold disease or disorder, the frequency, duration and intensity of migraine attacks can sometimes be moved up or down by various factors3. These include triggers and lifestyle choices.7 In an interview with the Migraine World Summit in 2021, Dr. Sait Ashina, assistant professor of neurology and anesthesia, discusses migraine as a threshold disease.15

Helpful Lifestyle Choices

The following behaviors and lifestyle choices are helpful in the prevention of migraine — and also good for overall brain health and longevity.

- Eat regular, healthy meals. Enjoy foods with a lower glycemic index.

- Stay hydrated.

- Limit alcohol.

- Be consistent with your caffeine intake.

- Avoid processed foods, additives, and coloring agents.

- Perform regular low-impact exercise.

- Get adequate, consistent sleep.

- Take part in meditative, mindful, and relaxing practices.

- Manage stress.

Sometimes, however, migraine can worsen despite all reasonable attempts to improve lifestyle choices. After all, some migraine triggers are unavoidable, such as hormonal fluctuations, unexpected stressful events, and the weather.

For more information on food triggers, view the video below featuring an interview with Dr. Vince Martin from the 2021 Migraine World Summit.

Silent Migraine and Medication

Medication for silent migraine is centered on the prevention of attacks and easing of symptoms. According to the International Headache Society’s newly released Global Practice Recommendations for Preventive Pharmacological Treatment of Migraine, preventive medicine is recommended for individuals when one or more of the following conditions are met.14

- The person has four or more attacks per month.

- Their migraine attacks have had an impact on their personal, social, or professional life.

- Their acute treatment proves ineffective.

- Their acute treatment has to be taken too often.

Preventive medications include:

- Blood pressure-lowering drugs, including beta-blockers like metoprolol (Lopressor) and propranolol (Inderal), and calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil (Verelan)

- Tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline and nortriptyline

- Calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies such as eptinezumab-jjmr (Vyepti), erenumab-aooe (Aimovig), fremanezumab-vfrm (Ajovy), and galcanezumab-gnlm (Emgality)

- Gepants like atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec ODT)

- Anti-seizure drugs like topiramate (Topamax) and valproate

- OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) shots

Medications that treat acute migraine attacks, include:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- NSAIDs such as Ibuprofen or Aspirin

- Anti-nausea medicines (antiemetics) like ondansetron (Zofran)

- Triptans such as eletriptan (Relpax) and sumatriptan (Imitrex)

- Gepants like rimegepant (Nurtec ODT), ubrogepant (Ubrelvy), and zavegepant nasal spray (Zavzpret)

- Lasmiditan (Reyvow)

- Dihydroergotamine (Migranal)

In the 2023 Migraine World Summit talk, “Beyond the Pain of Migraine Symptoms,” Dr. Nazia Karsan discusses possible advances in migraine treatment that could be on the horizon.11

Finding the right combination of medications for optimum silent migraine treatment, as well as prodrome and postdrome symptoms, may take some trial and error according to Dr. Karsan. She says, “I think incorporating those bothersome symptoms outside of headache, and perhaps outside of what we recognize as canonical migraine symptoms, will really take us forward in understanding how these drugs may work in that process.”

Silent Migraine Best Practices

- Track your migraine attacks with a headache diary, calendar, or app to better understand your triggers and how migraine affects you.

- Develop a migraine management plan in consultation with your doctor that is appropriate for the frequency and severity of your attacks. The plan may include acute treatment, preventive therapies, and lifestyle changes.

- If your condition does not improve or the burden of symptoms is high, consider consulting with a headache specialist via a referral for a more robust and comprehensive management plan.

- Remember that making changes to your lifestyle for migraine is also good for your overall brain health and longevity. None of us lead a perfect lifestyle, but to the extent we can make improvements, however small, to better manage stress, improve sleep, become more physically active, and make healthier food choices, the better for our overall health and well-being.

Takeaways

Silent migraine, or aura without headache, is a condition that causes aura symptoms, such as vision changes, sensorimotor changes, language changes and more, without the head pain of a typical migraine. The same factors that can trigger a classic migraine headache can also trigger a silent migraine, including weather changes, hormonal changes, stress, certain foods, dehydration, bright lights, and loud noises.

Managing silent migraine starts by understanding how migraine affects you, and developing an appropriate management plan in partnership with your doctor. Both lifestyle modifications and medication can help prevent and treat this condition.