Migraine is more than a headache

Migraine is a neurological condition, usually described as headache pain that is accompanied by symptoms such as light sensitivity, nausea and vomiting. However, a migraine attack can also be characterized by its phases, which begin before the headache pain starts, and continue even after the pain has disappeared.

“I think we do…patients a disservice, with migraine, [when] we bookend an attack by the beginning and the ending of the pain. The prodromal phase could last hours to days; the postdromal phase could last hours to days. So when you consider the true start of an attack and the true ending of an attack, [that] which was an eight, ten-hour headache may now turn into a three-day attack.”3

In this article we will describe:

- The four phases of migraine, their symptoms, and treatment options during each phase.

- A fifth phase of migraine, known as the interictal phase, that occurs between migraine attacks, and what treatments are important during this phase.

- Why it’s important to understand and identify the different phases of your migraine.

- The variability and complexity of migraine phases.

Phases of Migraine

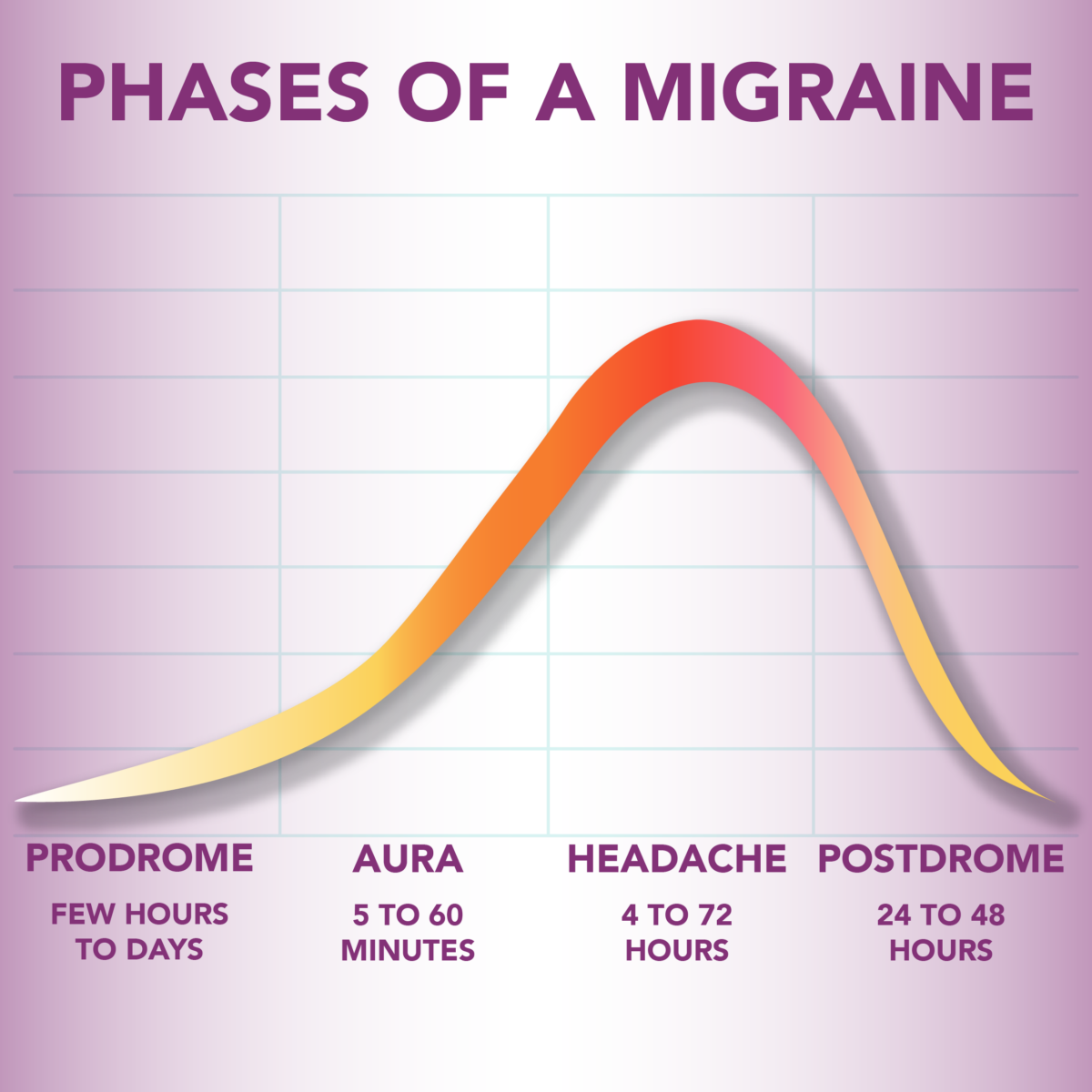

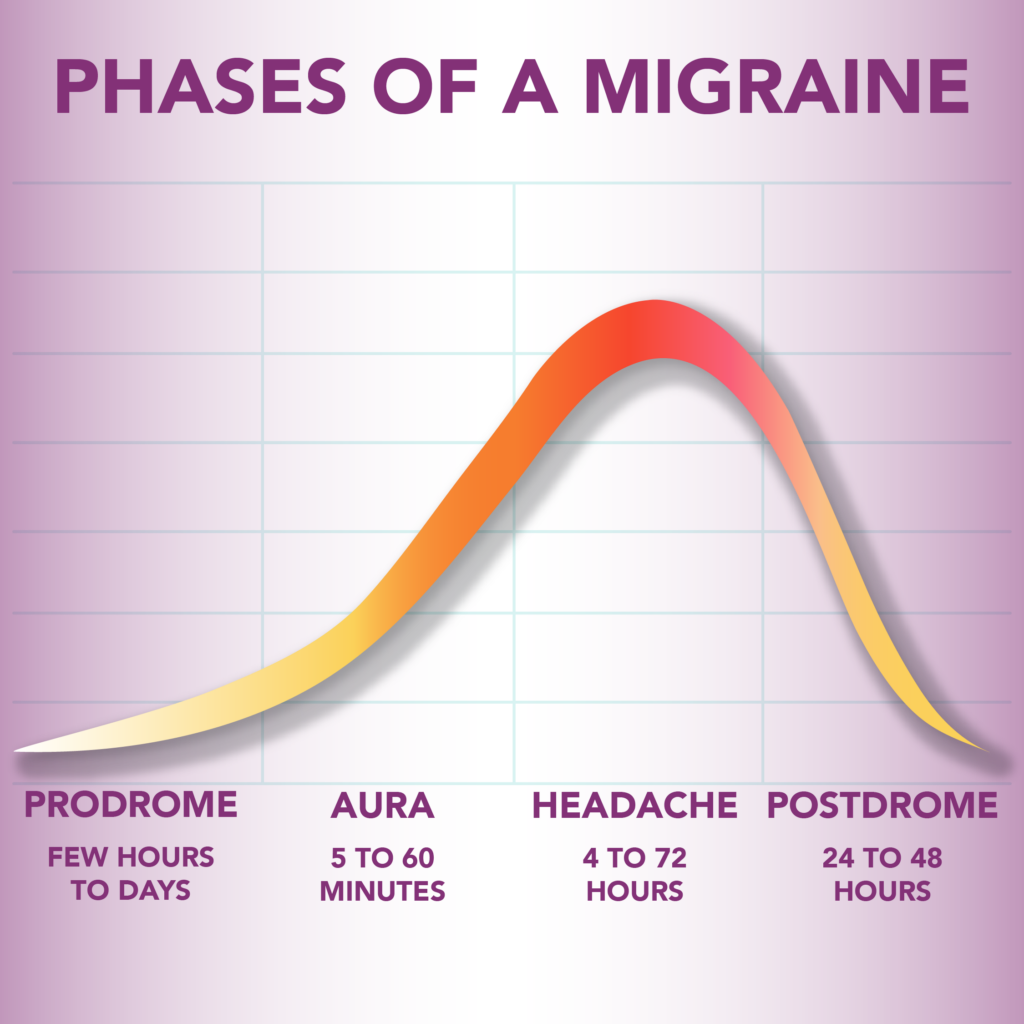

The four phases of migraine are:1

- Prodrome

- Aura

- Headache

- Postdrome

Prodrome

The prodrome phase refers to a set of symptoms that typically occur before the acute phase of the migraine attack. It begins anywhere from a few hours to a couple days before the migraine pain begins.2

Common prodromal symptoms of migraine include:1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

- brain fog, trouble concentrating, or difficulty processing information

- fatigue or tiredness

- food cravings

- frequent urination

- frequent yawning

- mood changes, such as depression, irritability, or elation

- nausea

- neck stiffness or pain

- sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- sensitivity to noise (phonophobia)

- sensitivity to smells (osmophobia)

- sleeping difficulties

Did you know?

The prodrome phase is also known as the premonitory phase. Premonitory means “serving to warn or notify beforehand” – a premonition that something is about to happen.8

Approximately 75% of people experience migraine prodrome symptoms, but they may be even more common.3 Lack of awareness and recognition of the prodrome phase can contribute to these symptoms not being identified as warning signs of an upcoming migraine attack.

More often, individuals with migraine disease identify bright lights, smells, neck pain, and other symptoms as migraine triggers. Distinguishing between migraine triggers and prodromal symptoms can be difficult, as Dr. Andrew Charles discusses in the video below:

In addition, prodrome symptoms can vary from attack to attack, making it even more difficult to identify a pattern. Prodromal symptoms are sometimes easier to identify in retrospect, or for family members to observe and identify.1

“Patients often experience a change in mood, either a feeling of depression or irritability, well before the headache begins. In fact, partners often can recognize [the mood change] more than patients.”1

Dr. Charles recommends that patients try the following interventions during the prodrome phase to see what impact they have on the progression of their migraine:1

- Take medication as soon as you recognize you’re in the prodrome phase. These may be over the counter anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) or prescription migraine medications.

- Try the following non-medicinal approaches, to see if they help:

- eat food and drink fluids, even when you are nauseated

- exercise

- breathing or relaxation techniques

However, at this time, there is no evidence that treatment of a migraine during the prodrome phase is helpful.5 According to Dr. Charles, “There’s no evidence yet to tell us what we should be doing during [the prodrome] phase of the attack … mainly because, [in] almost all of the trials for acute migraine medications, the stipulation is that they’d be taken when the pain has already started.”1

Aura

The second phase of migraine is the aura phase. This phase usually occurs about 30 minutes before the onset of the headache pain, but in some instances it may begin sooner or even overlap with the onset of the headache pain.5

Aura symptoms are due to an electrochemical event in the brain called cortical spreading depression. It starts in the occipital region in the back of the brain, and spreads toward the front, at a rate of 2 to 3 millimeters per minute. As this event spreads across the cortex, the symptoms occur.3 By definition, aura are symptoms that are not permanent, and must resolve within an hour. Aura that lasts for more than an hour is uncommon, and is referred to as migraine with prolonged aura.12

Dr. Charles describes four categories of migraine aura:5

- Visual aura, such as shimmering, zig-zagging, or colored lights, or blind spots in the vision. These visual disturbances spread across the field of vision over the course of 20 to 60 minutes.

- Sensory aura, such as tingling or numbness in the hand or face.

- Language aura, such as difficulty finding words or putting together coherent sentences.

- Motor aura, such as clumsiness or weakness on one side of the body.

For some people who experience aura, cortical spreading depression can cause aura symptoms to shift from one category of aura to another – for example, visual aura symptoms can spread into sensory aura symptoms.1

Auras, similar to other migraine symptoms, are variable across individuals, and also across migraine attacks. Approximately 30% of individuals have experienced aura at least one time, but only 15% of people experience aura with every migraine attack.3,5

The aura phase, similar to the prodrome phase, provides individuals with a warning signal that a migraine attack is coming. This is important, as early intervention can help mitigate the pain in the next phase of the attack. Prescription migraine medications, such as triptans, or non-prescription pain medications, such as NSAIDS, should be taken as soon as symptoms occur.12

Unfortunately, there are no specific treatments that are targeted just for aura. A small study has shown that taking a triptan may shorten the aura phase, but other studies have shown that taking a triptan during the aura phase is ineffective.12

Did you know?

Aura symptoms are not always followed by headache pain. This is sometimes unofficially referred to as “silent migraine.” It is common for a person who experiences aura to occasionally have a silent migraine. Only 3-4% of people are diagnosed with acephalgic migraine, which is when every migraine attack is a silent migraine.12

Headache

The headache phase of migraine usually follows the prodrome and/or aura phase. This phase can last for up to 72 hours. As the name of this phase suggests, this phase is most often characterized by head pain, which usually begins as mild and progresses to moderate or severe pain if it is not treated. The pain is often only on one side of the head, and may be throbbing, sharp, or dull. Usually the pain level peaks within 30 minutes. Additional common symptoms during the headache phase are:2,3,11

- insomnia or increased need for sleep

- low mood

- nausea or vomiting

- neck pain or stiffness

- sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- sensitivity to smells (osmophobia)

- sensitivity to sounds (phonophobia)

- vertigo or dizziness

This phase of migraine is usually called the “headache” phase or “pain” phase because head pain is the most common symptom. However, not everyone experiences headache pain during this phase. For example, those diagnosed with vestibular migraine often experience intense vertigo instead of pain.11 To represent the migraine experience for those who do not experience pain, this phase is sometimes referred to as the “attack” phase.

Did you know?

The headache phase of a migraine is also known as the ictal phase. The word ictal originates from the Latin word ictus which means “a blow or a stroke.”10

As mentioned previously, studies have shown that the earlier you treat a migraine during this phase, the more likely that acute treatment will be effective. It is recommended to take acute treatments for headache pain and/or nausea immediately when these symptoms start.1 Early treatment is not only important in shortening the duration of the headache phase, but it is also important in preventing future migraine attacks.5

Treatments during this phase are usually focused on reducing the pain or discomfort. Migraine treatments may include, but are not limited to, the following categories, and are sometimes used in combination:4,9

- over-the-counter medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or naproxen, or pain relievers like acetaminophen

- prescription migraine medications, such as triptans, gepants, ditans, and ergotamine derivatives

- anti-nausea medications (antiemetics)

- cold therapy to treat neck pain or stiffness

However, frequent use of acute medications – more than 10-15 doses per month – can result in medication overuse headache. This is when regular use of acute pain medications triggers future migraine attacks.9

Postdrome

The postdrome phase occurs after the headache phase has resolved. This phase may be unofficially known as the “migraine hangover.” It’s dominated by cognitive symptoms, such as:2,4,11

- difficulty concentrating

- disorientation or dizziness

- fatigue, or feeling “washed out” or “hungover”

- low mood

- neck pain

Migraine postdrome symptoms can last for a few days or in some cases up to a few weeks, and can be just as disabling as the headache phase.1,11

“It’s all about … returning [migraine patients] to normal function or near-normal function. … If I can’t function because I’m in a postdrome, it’s just as debilitating as if I’m having pain.”3

No specific treatments have been identified for the postdrome phase, though the following may be helpful in some cases:1,4

- caffeine (unless it is a migraine trigger)

- cold therapy or heating pads to treat neck pain or stiffness

- prescription drug stimulants, such as drugs that address the neurotransmitter norepinephrine

- rest or sleep

Interictal

The time between migraine attacks – between the end of the postdrome phase and the beginning of a prodrome phase of the next attack – is known as the interictal phase. Migraine symptoms may still persist during this phase, such as:11,13

- light sensitivity, especially in individuals with chronic migraine

- lightheadedness or dizziness, especially in individuals with vestibular migraine

- nausea

- sensitivity to sound and/or odors

“We go back to the fact that migraine is not a headache. Migraine is a brain disease, and it impacts many different aspects of our brain and how we function. And so, an individual whose head pain is gone, still can have lingering symptoms in between.”14

Migraine symptoms during the interictal phase are an important indication of the progression of migraine disease. For example, untreated episodic migraine can progress to chronic migraine, as consecutive migraine attacks begin to overlap each other and the individual is unable to fully recover from one migraine attack before the next one begins. This is characterized by worsening interictal symptoms. As Dr. Lay explains in the video below, reducing migraine symptoms during the interictal phase can be a step toward improving a person’s migraine disease.11,14

The interictal phase is a time to focus on migraine prevention and lifestyle. Preventive medications may be necessary to decrease the frequency of migraine from chronic to episodic. However, preventive medications do not need to be taken forever; they can be used temporarily to “reset the brain” and break the cycle of frequent attacks.14 Then, the progress that was made with the preventive medications can be anchored by lifestyle modifications, such as:7,14

- biofeedback, meditation, and relaxation techniques

- consistent eating schedule

- consistent sleep schedule, or good “sleep hygiene”

- exercise

- hydration

- nutraceutical supplements

“Extremes of exposure tend to bring on headaches. …Deviations from your daily pattern tend to bring on a headache. …”

Individuals with migraine may instinctively focus on avoiding migraine triggers. However, as Dr. Vince Martin points out, trigger avoidance isn’t always practical, and there may even be some benefits in intentional trigger exposure to train the body to cope with migraine triggers:7

Your experience with migraine is unique and likely to change over time

You – and your migraine attacks – are unique. It’s important to emphasize that not everyone with migraine experiences all of the four phases of migraine, nor will they experience every phase, in the same order, with every migraine attack. These phases can blur together, change order, change duration, change intensity, or be skipped altogether.1,2,3,5 Every migraine condition is unique, just as every individual with migraine is unique.

However, understanding the phases of migraine can help us treat our symptoms more effectively, decrease our migraine frequency, and, as Dr. Lay explains, change our brain structure over time:14

“We definitely do see alterations in the structure of the brain [due to chronic pain], and it’s not completely well understood why those happen and what the physiology is to get patients there. But we do know that you can change it the other way. We don’t really fully understand how or why, but we do know that doing all the right things – so, lifestyle factors, nutraceuticals, getting out for a walk, mindfulness, meditation, treating your attacks when they come, getting on top of them early and looking at preventive therapy – all are really important to reverse from chronic migraine to episodic migraine, but also to reverse some of those brain changes.”