- Migraine and Mental Health

- The Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression Relationship

- Key Features of Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

- Contributing Factors of Migraine and Mental Illness Comorbidities

- Treatment of Migraine and Co-occurring Anxiety and Depression

- Challenges of Living with Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

- Looking Ahead: Coping with Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

- Additional Resources

“Mind over matter”—simple, yet not easy.

For individuals living with migraine disease and its psychological comorbidities, coping with both the physical and mental symptoms can be very challenging. Despite this variable experience, a ‘mind versus body’ approach is a false dichotomy. In actuality, migraine and mental illness pool from undercurrents infused with similar biological make-ups. This resulting interdependence marks migraine and mental illness as travel companions and comorbid conditions.

Migraine and Mental Health

The pain, isolation, and frustration of living with migraine disease is a burden shouldered by one billion people worldwide.1 When this burden becomes impacted by mental illness, disability rises, leaving many with mental illnesses interlocked with migraine, and subsequently migraine restricted to maladaptive mental states.

Occurring silently, invisibly, and often in the face of stigma, migraine and psychiatric disorders are underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood.2

Mental Illnesses Comorbid with Migraine

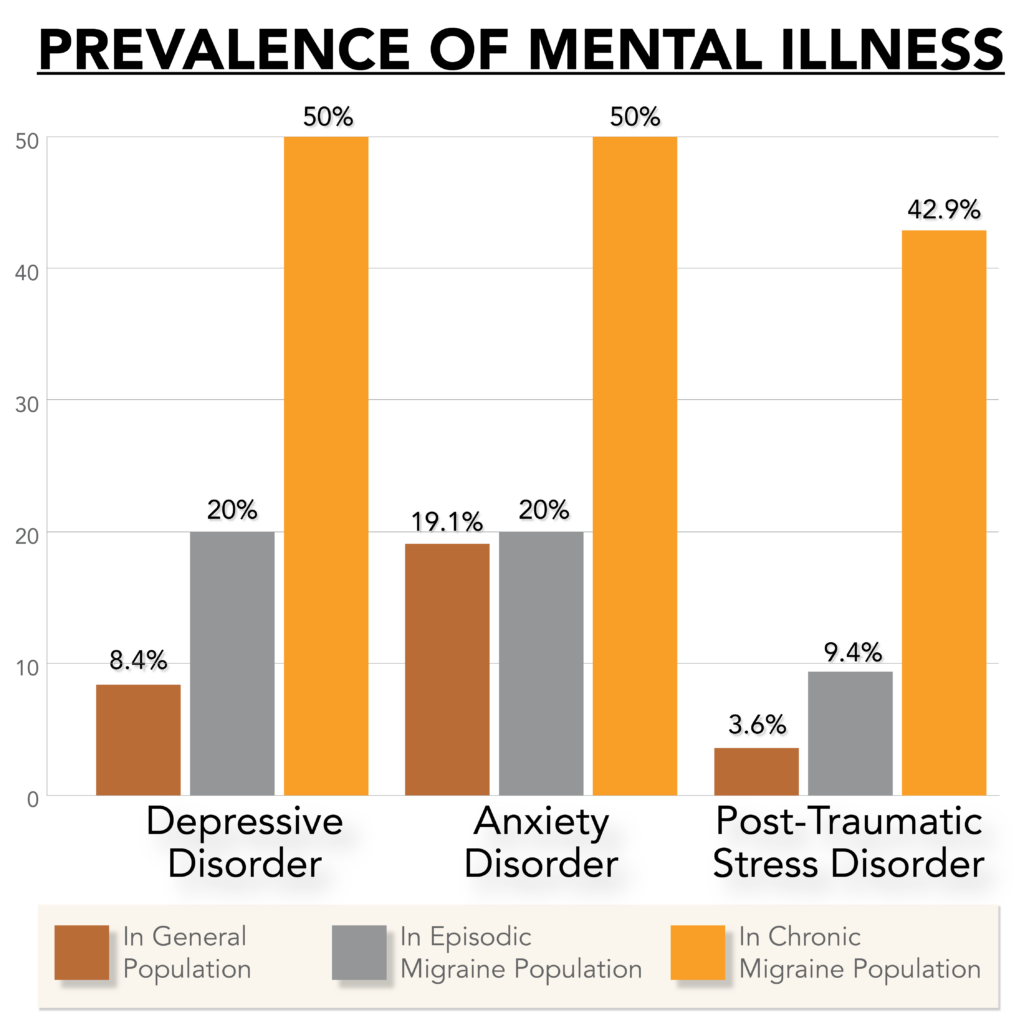

Although migraine is neurobiological in nature, psychological disorders may arise in conjunction with migraine due to shared genetic and environmental components. This overlap in origin, as well as presentation, accounts for the occurrence of several mental illnesses comorbid with migraine, i.e., occurring simultaneously at a higher than chance rate.3

Mood Disorders

Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the medical term for what is typically referred to as depression. Like migraine, depression is one of the leading causes of global disability. Severe depression can incapacitate just like migraine, and individuals with migraine are five times more likely to develop depression than those without migraine.3

Those with MDD experience persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest. Coupled with somatic symptoms, such as changes in appetite, sleep, and energy, depression interferes with daily life and produces general feelings of unhappiness or not wanting to live.4

Although “depression headaches” may be used as a descriptor of experience, it is not the medically used term. Nevertheless, migraine and MDD may present in a similar fashion, as both can impair cognitive and physical function.

Bipolar Disorder

Like migraine, bipolar disorder rests on a spectrum, and individuals with bipolar disorder experience a range of symptoms, both in type and severity.

Although intensity of symptoms vary, bipolar disorder causes shifts in mood, energy, and ability to function. Episodes of mania or hypomania involve elevated, expansive, or irritable moods, while depressive episodes are marked by sadness, hopelessness, or indifference.

The road to a bipolar diagnosis can take years, echoing the journey that many with migraine face. In addition, one third of people with bipolar disorder also have migraine, making bipolar disorder yet another migraine comorbidity.5

Anxiety Disorders

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

The hallmark symptom of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)—excessive, uncontrollable, and persistent anxiety and worry—is not unfamiliar to those prone to frequent migraine attacks. GAD has a five-fold greater prevalence in the migraine community. The chronicity of migraine and GAD affects an individual’s participation in work, school, and social life. These impacts perpetuate a cycle of fear and anxiety.

Becoming increasingly sensitive to your own physiological cues ties both disorders together as well, and understandably so. Efforts to manage these disorders often leave people with migraine and GAD with heightened interoceptive awareness, or the ability to notice bodily sensations.5

Rises in stress can worsen both disorders, causing increased worry, withdrawal, and hopelessness.3 Individuals who experience migraine and co-occurring GAD often become so conditioned to negative outcomes that catastrophizing becomes a learned response, and one that affects treatment outcomes.7

Panic Disorder

The symptoms of panic disorder parallel many of the experiences people with migraine face, including severe, intermittent, unpredictable, and uncontrollable attacks. Rushes of adrenaline and anxiety accompanied by a range of mental and physical symptoms mark the frightening experience of panic attacks.5

Efforts to decrease the frequency and impact of these attacks often result in avoidance and hypervigilance, experiences not uncommon amongst those with migraine. These resemblances contribute to the increased prevalence of panic disorder in the migraine population, as individuals with migraine are three to ten times more likely to develop it than those without migraine.3

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Feelings of fear or distress are natural responses to trauma. However, nine million Americans experience lasting negative emotional responses after exposure to a traumatic event. This prolonged problem is referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).8

Individuals with PTSD experience intrusive and distressing thoughts and flashbacks, and as a result, often engage in avoidant behaviors as a way to decrease the frequency and impact of these symptoms. In addition, feelings of self-blame and other negative emotions contribute to low moods and indifference. Like migraine, changes in arousal, such as cognitive difficulties, sleep disturbances, and hypervigilance, color the experiences of those with PTSD.8

Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation refers to the broad range of thoughts, ideas, and desires related to death and suicide. From momentary passive thoughts to deliberate planning and intense fixations, suicidal ideations vary in intensity, length, and type.

Because the probability of suicidal ideation increases with the presence of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder (disorders which already coexist with migraine), suicidal thoughts are more common within the migraine population.5 Not only that, but suicide attempts occur two-and-a-half times more among people with migraine than those without.2,3

The Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression Relationship

Bidirectionality

Experiencing depression or anxiety alongside migraine is not uncommon—many individuals with these disorders have witnessed neurological dysfunction leak into new territory. This highlights a bidirectional relationship: people with migraine are more likely to develop depression or anxiety than the general population, and vice versa.3,5

Migraine, depression, and anxiety feed off of each other—having one may worsen the others. Conversely, successful treatment of one condition may, but not always, ameliorate symptoms of the other conditions.

They work in tandem, for better or worse, and in this way they often travel together. More often than not, though, this pairing starts with migraine, and the addition of depression or anxiety arises later.5

Did You Know?

People with depression are three times more likely to develop migraine than people without depression.3

Risk Factors for Developing Mental Illness Comorbidities

Although migraine and mental illness coexist separately, there are several factors that increase the risk of developing mental disorders alongside migraine.

Stress

Living with migraine is stressful. According to the Chronic Migraine and Epidemiology Outcomes (CaMEO) Study, people living with migraine experience notable amounts of stress and guilt.7 Heightened psychological distress, such as worry, fear, or hopelessness, not only trigger migraine attacks, but also the development of comorbid anxiety and mood disorders.3

This link is mediated through activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the “flight or flight response.” Changes in this neural circuitry creates physiological imbalances that can manifest as anxiety or depression. Cognition, decision-making, and mood all become indicated in maladaptive patterns, perpetuating a vicious cycle where migraine and mental illness become relational and intertwined.7

History of Abuse or Neglect

The long-term consequences of abuse or neglect result in dysregulation of the body’s response to stress, increasing levels of stress hormones and inflammation.

In addition to changes in stress reactivity, the emotional impacts of childhood trauma contribute to negative emotional states. Consequently, those with a history of abuse or neglect are at a higher risk of developing both migraine and mental illness.10

Emotional Abuse

While all forms of abuse or neglect can contribute to the development of illness, emotional abuse in particular is associated with migraine. People who have experienced emotional abuse in childhood also experience more significant impacts from the typical stressors found in adulthood.10

Increased Headache Frequency

As the frequency of migraine attacks increases, so does the risk for developing anxiety and mood disorders.3,5

Individuals with chronic daily headache are seven times more likely to develop depression, while those with one or fewer attacks per week are only twice as likely.10

It is believed this correlation is two-fold:

- Experiencing more pain and disability, which are unpredictable in nature, can cause heightened psychological distress and social isolation, and thus increased risk for the development of mental illness.3,5

- Increased migraine attacks can cause central sensitization, or the hypersensitivity of the central nervous system to stimuli. These sensitized neural networks can cause further distress, both physical and emotional, thereby increasing the risk of developing a mental illness.11

Furthermore, similar to frequency, increased headache severity accounts for the rise in suicidal ideation within the migraine population.5

Migraine with Aura

Migraine with aura has been linked to both depression and panic disorder, and those who experience aura are three times more likely to develop bipolar disorder than the general population.11 In addition, migraine with aura has been shown to be associated with suicide attempts.12

Poor Sleep

People with migraine report more sleep problems than those without migraine.13 While sleep disturbances are symptomatic of many mental illnesses, they may also be a risk factor, as poor sleep quality can result in fatigue, both physically and mentally. Irritability and exhaustion negatively affect emotional regulation, leading to mood swings and other physiological manifestations as seen in anxiety and depression.2,4

Summary

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Migraine and Mental Illness

Migraine is comorbid with various mental disorders, including major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bipolar spectrum disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation.

These disorders co-occur with migraine at a higher-than-chance rate and have a bidirectional relationship with migraine. For example, people with migraine are more likely to have depression or anxiety than those without migraine, and vice versa.

In individuals with migraine, certain risk factors increase the chance of developing a mental illness. These include migraine with aura, increased stress and headache frequency, poor sleep, and a history of abuse or neglect, particularly emotional abuse.

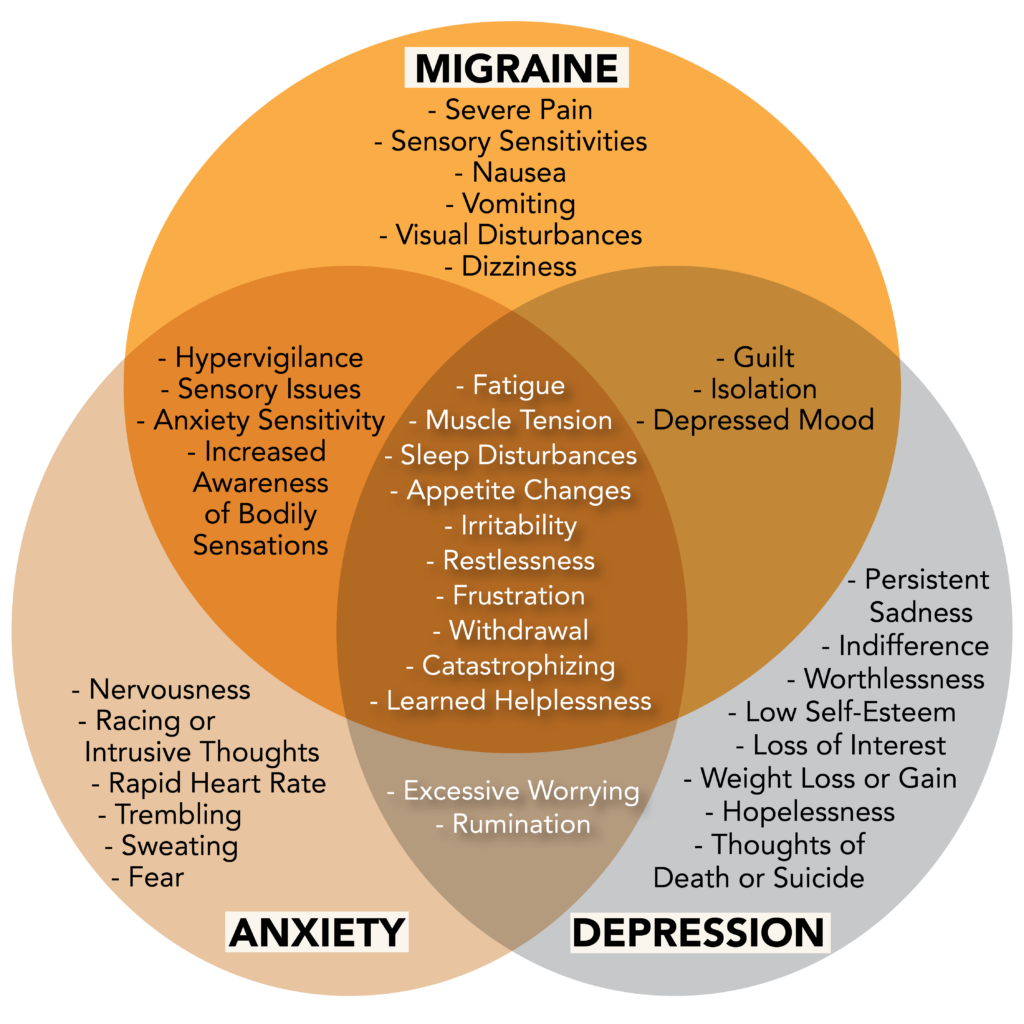

Key Features of Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

Neurological Dysregulation/Imbalance

While a well-honed stress response has evolutionary advantages, repeated activation of the sympathetic nervous system can cause dysregulation and somatization. Somatization refers to the physical expression of symptoms arising from emotional distress. Because the body cannot distinguish external dangers from internal worries, this stress response can fire frequently in the presence of migraine and mental illness, where internal tension and uncomfortable emotions may run high.

Stress Reactivity

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis regulates the body’s response to stress through intricate feedback loops between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal gland. This neuroendocrine network modulates various processes involving the immune system, nervous system, and metabolism, all in efforts to regain stability and maintain homeostasis, or internal equilibrium.

Stressors of any nature—emotional, physical, or mental—activate the HPA axis and jumpstart a cascade of events that result in the release of various hormones, including cortisol, a stress hormone.

When efforts to maintain homeostasis through the HPA axis result in allostatic overload, or the negative consequences associated with constant sympathetic nervous system activation, the nervous system becomes hyperexcitable and easily aroused. Abnormal and heightened responses to stressors, such as pain and uncomfortable emotions, further dysregulate neural circuitry and increase stress reactivity.15

Behavioral Patterns

Living with migraine, anxiety, or depression can deleteriously restructure cognition and misalign behavior. These impacts interfere with the development of healthy coping strategies and positive self-talk.

Though dysfunctional and unhelpful, these behavioral patterns can be viewed as understandable reactions to untenable circumstances. Excruciating pain, debilitation, and uncomfortable moods and emotions, as seen in migraine and mental illness, challenge coping mechanisms and adaptability.

Negative Self-Talk: Catastrophizing

Becoming accustomed to negative outcomes when living with chronic diseases often leaves individuals with migraine or mental illness prepared for the worst case scenario.

Catastrophizing refers to the snowballing of thoughts that escalates current conditions into disastrous consequences. This thought process lowers self-efficacy and the belief that people have control over their disease. As a result, fear and increased stress thwarts successful treatment outcomes.

Common among individuals with migraine, anxiety, depression, PTSD, and panic disorder, catastrophizing fuels feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and worry. Rumination and heightened preoccupation with uncomfortable emotions or sensations accentuate symptoms of migraine, anxiety, and depression. In addition, frequent catastrophizing can propel the progression of episodic to chronic migraine.3,7

Anticipatory Anxiety and Hypervigilance

Inhabiting a body that experiences uncontrolled, unpredictable, and painful migraine attacks is inherently stressful. This is true for any chronic pain or disability with variable and acute attacks. Uncertainty of the future can lead people with migraine and mental illness to feel “on edge,” and understandably so.

Adapting to this erratic nature can result in a marked level of hypervigilance, and worry for the next migraine attack or the inability to be fully present and engaged can lead to anticipatory anxiety.5,6 Living constantly “on guard” can leave people with migraine and mental illness feeling stressed and exhausted.

Although understandable, these thought processes stamp the future as fixed. Attempts to control the uncontrollable can narrow one’s perspective, impair function, and shrink hope.

Anxiety Sensitivity

Due to the effects of anxiety and hypervigilance, people with migraine and mental illness can become increasingly sensitive to their own physiological cues.5

Developing anxiety sensitivity, or the fear of bodily sensations associated with anxiety or migraine, can increase the stress response and attack severity. It may also decrease the desired response to medication.5

Learned Helplessness

Feelings of frustration and exhaustion can dampen the belief we have power over illness. Repeated stressful experiences can leave individuals with migraine or mental illness feeling trapped and unable to fulfill personal or professional obligations despite their best efforts. Over time, as functioning lessens, an individual’s spirits may follow.

Learned helplessness, or the conditioned belief that stressful situations cannot be changed despite being given opportunities to do so, is directly tied to migraine, depression, and anxiety. Believing one is incapable of affecting change lowers motivation, frustration tolerance, and self-esteem. Without belief in oneself, helpful intervention and treatment may remain distant and unutilized.6

Summary

What are the Similarities of Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression?

The key features of migraine and mental illness, increased stress reactivity and cognitive-behavioral patterns, are rooted in neurological dysfunction. This dysfunction appears physiologically through overactivity of the HPA axis, as well as behaviorally through self-defeating psychological patterns.

Examples of such patterns include catastrophization and anticipatory anxiety, in which people anticipate negative outcomes. Additionally, feelings of hypervigilance coupled with a heightened ability to sense bodily sensations, or anxiety sensitivity, is common amongst those with migraine, anxiety, and depression. Over time, feelings of discouragement and disappointment can potentially contribute to learned helplessness, or the belief that individuals are incapable of affecting positive change despite being given opportunities to do so.

Contributing Factors of Migraine and Mental Illness Comorbidities

Biological Components

Like migraine, the roots of mental illness cannot clearly be attributed to any singular cause. Nevertheless, these conditions share overlapping chemical imbalances, hormonal influences, and genetic susceptibilities.3,16

Neurotransmitter Dysregulation

Neurotransmitters are chemical substances that the nervous system uses to transmit messages between nerve cells and target cells. They play an important role in a range of everyday functioning and behavior.2,3

Serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) are believed to be involved in mood, pain tolerance, motivation, and concentration. In addition, glutamate and GABA function as complements by acting as excitatory and inhibitory nervous system agents.19

Hormonal Influences

Similar to neurotransmitters, hormones are chemical messengers that affect different bodily processes such as metabolism, sexual function, reproduction, and mood.

The association between female hormones and migraine is strong—fluctuations in certain hormones can cause spikes in migraine attacks, as well as anxiety, mood swings, fatigue, and irritability, as seen in premenstrual dysphoric disorder.18,33

The hormonal link may account for the increased prevalence of migraine and depression in people with vaginas as compared to those with penises.17

Genetic Associations

Genes affecting the function of some neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, may be implicated in migraine, anxiety, and depression.

This overlap in origin predisposes those with headache disorder to mental illness and vice versa.11,16

Environmental Stressors and Impacts

Stress is a normal state of humans. However, prolonged negative emotional, physical, or mental responses to stressors, or changes in the environment, has biological ramifications.10

Trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences

Approximately 45% of the adult population have experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the form of abuse or neglect. These traumatic experiences affect developing brains and bodies, causing increased risk for physical and mental health conditions.10

Functional Changes

HPA Axis Dysregulation

Chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system results in an interruption and dysregulation of the HPA axis, the body’s stress response system.10

Living in survival mode not only thwarts the ability to thrive, but also overloads the body with chemical substances called glucocorticoids which affect neural communication and connectivity. This can lead to a myriad of physical and mental symptoms.7,10

Inflammation

While optimal levels of glucocorticoids have anti-inflammatory effects, excessive levels of these hormones, which occur due to HPA overactivity, can actually increase inflammation. This maladaptive mechanism results in higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein have been found in individuals with a history of abuse.10

Structural Changes

The increased levels of glucocorticoids found in individuals who experienced high stress during childhood can cause shrinkage of the dendrites, or communicative branches of neurons, and its corresponding brain structure.

Volumetric changes to the limbic system, including the hippocampus and amygdala, which are involved in memory and fear, is associated with trauma and high childhood stress.10

Epigenetic Changes

Epigenetics refers to the relationship between the environment, behavior, and genes.

Exposure to trauma or ACEs affects the epigenome, which are chemical compounds that govern how a particular gene functions. With epigenetic changes, DNA sequence remains unaltered, but genetic expression undergoes modification, resulting in either up or down regulation of certain genes.10

Did You Know?

Due to the profound effects of early life stress, experiencing trauma and ACEs has the potential to affect multiple genes, and therefore multiple systems. Additionally, because epigenetic changes are hereditary, unresolved trauma can be passed down through generations. These devastating impacts of ACEs shed light on the reality of generational trauma.10

Summary

What Causes Migraine and Mental Illness Comorbidity?

While there is no singular cause for migraine and mental illness comorbidity, a variety of biological and environmental factors contribute to its concurrence.

Overlapping genetic associations, chemical imbalances, and hormonal influences can enable neurological dysfunction, thereby creating conditions ripe for comorbidity. Additionally, environmental factors, such as trauma and adverse childhood experiences can cause functional, structural, and epigenetic changes that contribute to migraine and mental illness onset.

These internal and external forces drive the genesis and progression of migraine, anxiety, and depression by affecting stress reactivity and inflammatory responses.

Treatment of Migraine and Co-occurring Anxiety and Depression

Pharmacological Intervention

The most effective medications to preventively treat both depression and migraine are antidepressants.

Antidepressants

Antidepressant medications work by affecting certain neurotransmitters that play a role in mood and pain, such as serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline.3,18,19

There are several classes of antidepressants that may be considered:

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline (Elavil) and nortriptyline (Pamelor)

- SNRIs (Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors), such as venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), such as fluoxetine (Prozac)

When used appropriately, antidepressants can be effective treatment. Efficacy will vary depending on the individual patient and tolerability to side effects.

Non-Pharmacological Intervention

“…if you don’t treat the whole person, you’re oftentimes not going to succeed in treating each aspect of the person.”2

Due to the increased stress present in neurological dysfunction, realigning the body’s stress response is a cornerstone of migraine and mental illness management.

Fortunately, this can be achieved in a number of ways, and integrating multiple behavioral therapies and techniques can decrease stress and recalibrate our emotional response.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy with a trained mental health professional provides a safe space to process and address the challenges of living with migraine and comorbid depression or anxiety. Although there are numerous therapeutic modalities, two have strong evidence for migraine and mental health issues:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the relationship between emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. The focus of CBT lies in what can be controlled and adjusted, which is our reaction and response to the unpredictable and uncontrollable aspects of migraine and mental illness.3,7,20

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) helps individuals accept uncomfortable emotions while staying present and nonjudgmental. By developing more productive approaches to cope with stress, people can commit to take action in ways that better align with their values and goals.4,21

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a therapeutic technique that trains people to control physiological processes that usually occur involuntarily, such as heart rate, blood flow, and muscle tension. Sensors attached to the scalp, hands, and chest provide visual or auditory feedback, allowing the individual to see in real-time how their thoughts affect bodily functions.

By increasing self-awareness and self-regulation, sympathetic nervous system activity can drop, thereby decreasing the body’s stress response. This relaxation process can then be applied to real-life circumstances that trigger or provoke migraine attacks or depressive and anxious symptoms.5,6,7

Relaxation Training

Although stress is unavoidable, relaxation training can help us modify how we respond to stressors. By slowing down the body’s stress response, calmness and rest can be achieved through regular practice.16

A few examples of relaxation therapies include:

- Breath work: slow, abdominal, diaphragmatic breathing has evidence-backed benefits for migraine and anxiety disorders.

- Progressive muscle relaxation: this technique involves contraction followed by relaxation of muscle groups. It helps people gain better awareness and ability to release muscle tension.

- Guided imagery: by envisioning helpful mental images, individuals can learn to navigate uncomfortable terrains with positivity and openness.

Meditation

Meditation is an ancient practice that redirects attention and awareness by grounding the senses in a thought or activity, such as the breath. As breathing slows and regulates, internal chatter fades, and a sense of clarity and calmness can be achieved.

By noticing thoughts and letting them pass, individuals can learn to quiet their mind, decrease stress, and regulate their emotions, all of which can positively affect migraine and co-morbid mental illness.

Mindfulness Based Therapies

“They say that depressed people live in the past; anxious people worry about the future. So, the role of mindfulness is to be in the present.”2

Mindfulness is a technique that focuses on the present moment in a nonjudgmental way. Mindfulness-based approaches nourish acceptance and understanding of a negative experience, thereby ushering in appropriate action.

Mindfulness-based therapies beneficial for migraine and comorbid mental illness include:

- Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): MBSR includes a variety of approaches, such as yoga or meditation, that decrease stress and increase resilience.

- Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT): This modality combines the pillars of CBT and MBSR and is especially helpful for the prevention of depression relapses.

Lifestyle Changes

In order to integrate behavioral therapies and maximize their benefits, healthy lifestyle changes should be prioritized.

Addressing Physiological Needs

“If you don’t sleep well, if you don’t eat well, it’s hard to feel well.”2

Developing healthy habits facilitates brain plasticity, or the brain’s ability to adapt and change. Nourishing food, adequate sleep, ample hydration, and accessible movement can help promote neuroplasticity by releasing the patterns and stress responses present in migraine comorbid mental illnesses.3,24

Increasing Social Support

“…a lack of social support is inherently stressful. We need support from the people around us.”20

When the impacts of migraine are compacted by those of depression or anxiety, social support may wither, and individuals may experience increased isolation and disconnection.

Social support can take various forms. Compassion, helpful advice, and support groups can all provide the much needed connection that bolsters self-esteem and buffers against stress, one of migraine and mental illness’s biggest triggers.6,16

Summary

How is Migraine and Comorbid Depression and Anxiety Treated?

Effective management of migraine and comorbid depression and anxiety involves a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options.

Antidepressants and psychotherapy are often used simultaneously to recalibrate chemical imbalance and regulate stress. Other modalities such as biofeedback, meditation, mindfulness, and relaxation therapies aid in realigning physiological and emotional responses to stress, especially when used concurrently with healthy lifestyle changes and social support.

Using varied approaches, medicinal and behavioral, offer individuals the best chance of successful treatment.

Challenges of Living with Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

Misconceptions and Stigma

“Migraine is not your fault. Migraine is a disease of the nervous system.”25

Migraine and mental disorders share more in common than neurological dysfunction. The misconceptions, judgments, and negative biases surrounding both disorders contribute to stigma, or the unfair and harmful labeling associated with a group of people who have a particular trait or disease.

The resulting self-blame, guilt, and shame compound the difficulties those with migraine and mental illness already face. These hardships lead to increased isolation, disability, and psychological distress.1,26,27

Increased Risk of Developing Other Medical Conditions

When people experience the far-reaching impacts of migraine disease in conjunction with mental illness, their quality of life may decrease. As a result, increased stress and isolation can contribute to the development of other health conditions.28

In particular, people with migraine and a history of trauma are at an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease, PTSD, suicidal ideation, as well as revictimization.10,29

Worsening of Migraine and Mental Illness

People who have experienced stigma or discrimination may hesitate sharing health concerns with their physician. Delays in treatment can make migraine harder to manage, and within the time that passes until treatment is received, mental health issues and migraine can worsen.30

Moreover, people with episodic migraine and a history of abuse or comorbid psychiatric conditions are at a greater risk of developing chronic migraine.10,16 Not only that, but the risk of developing medication overuse headache also increases with the presence of depression or anxiety.2

In addition to chronicity, encountering stigma can lower self-esteem and provoke symptoms of depression or anxiety, contributing to negative cognitive-behavioral patterns.

Treatment Obstacles

Successful treatment of migraine and co-occurring mental illness requires patient engagement and participation. Apathy, lethargy, and indecisiveness, as often seen in depression, hinder a patient’s ability to incorporate new skills and healthy lifestyle changes. As a result, recovery and treatment outcomes can become stunted.

Due to stigma’s silencing effects, those experiencing migraine and mental health issues may refrain from disclosing the challenges they are facing. Although done out of self-protection, nondisclosure prevents individuals from receiving timely and appropriate treatment.31

Summary

What are the Challenges of Living with Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression?

Individuals living with migraine and comorbid anxiety or mood disorders are at risk for increased disability and a poorer quality of life.

Experiencing stigma can result in distress and nondisclosure. Consequently, delays in treatment can worsen symptoms of depression and anxiety and trigger the development of other health conditions.

Individuals with a history of abuse or psychiatric conditions are at an increased risk of revictimization and developing chronic migraine, as well as other diseases. A lack of patient willingness, engagement, and proactivity, as often seen in depression, can interfere with successful treatment outcomes.

Looking Ahead: Coping with Migraine, Anxiety, and Depression

Learned Optimism

Sitting in direct opposition to learned helplessness is learned optimism. In contrast to the pessimism and unwillingness that governs learned helplessness, optimistic people utilize adversity as a powerful weapon of growth to affect beneficial change through intentional and mindful thoughts and behavior.

By viewing setbacks as avenues of potential rather than dead ends, those who are optimistic tolerate and cope with stressors more effectively. They not only experience less stress, but are also able to recover from stressors more quickly. Additionally, less overwhelm and discouragement allow space for resilience: a key component of disease management.6

Resilience Training

Resilience refers to the strategies and coping tools used during times of hardship. While innate personality styles may differ from person to person, resilience can be learned and cultivated regardless of background or circumstance.7

Building resilience, or resilience training, acts as a buffer against stressors, and the more resilient you become, the less suffering you may endure.

Ways to boost resilience include:

- educating yourself

- building your support system

- implementing healthy lifestyle changes

- incorporating behavioral therapies

- developing passions and purpose outside of disease

- engaging in advocacy

By releasing what no longer serves you and welcoming positivity, people with migraine, anxiety, and depression can navigate remission and relapse with increased confidence, thereby boosting resilience and optimism.

Bottom Line

Migraine and mental illness share a bidirectional relationship driven by neurological dysfunction. Major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, the most common mental illnesses within the migraine community, are five-fold greater in the migraine population than the general population.

While certain physiological and environmental factors increase the risk of developing comorbid mental illness, underlying biological indications create conditions ripe for comorbidity. Trauma exposure and increased stress reactivity compound these implications, resulting in heightened disability and distress.

Realigning the dysfunctional stress response present in migraine, anxiety, and depression is paramount to successful treatment. Through medications and behavioral interventions, significant progress can be made, and new coping strategies can be developed. Cultivating resilience and learned optimism through this process bolsters our capacity to manage stressors and improves our wellbeing.

FAQs

Additional Resources

- For psychotherapy, biofeedback, and relaxation resources, visit https://dawnbuse.com/resources/

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder:

- Suicide Hotline:

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Tel: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Books:

- “The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook” by Martha Davis

- “Authentic Happiness” by Martin E.P. Seligman

- “Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life” by Martin E.P. Seligman

- Other:

- Martin E.P. Seligman’s PERMA Theory for happiness and well-being

- Podcasts focusing on migraine and mental health

- Patient Health Questionnaires for Psychological Disorders

Links to outside organizations and articles are provided for informational purposes only and imply no endorsement on behalf of Migraine World Summit.